Today in Grosse Pointe high school students and those all across the state will convene to take the ACT test. They will no doubt be conscious of the significance of this test on their college aspirations. Thankfully they won’t be burdened with the implications those results might have on so many other people.

In September 2010, I published “Reframing Disparity: Accountability Meets the Achievement Gap” in which I argued that the continued momentum of the high stakes standardized testing movement needs to be reconciled with the undeniable trend that students of lower socioeconomic status statistically do not perform as well on those tests. I wanted to reframe the Achievement Gap in socioeconomic rather than a racial terms.

The Achievement Gap is relevant across our district, the state, the country, and even the world. All parties – particularly parents and policy makers – need to be conscious of it, particularly at this juncture when the prevailing education reform sentiment seeks to place increasing emphasis on standardized test results.

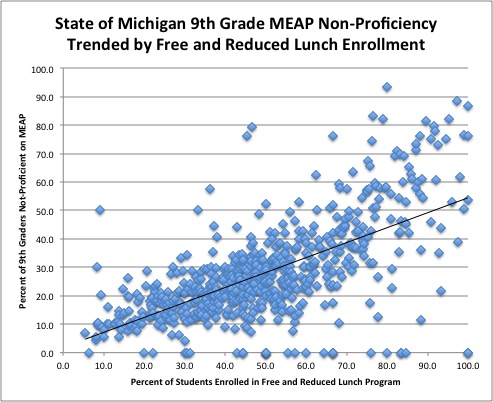

To obtain a graphical snapshot of the correlation between standardized test scores and economic level, I plotted all Michigan school districts’ percent of student non-proficiency (read this entry for a note on proficiency) on the 9th grade MEAP standardized test against the percent of students in those same districts who are enrolled in the federal Free and Reduced Lunch (FRL) program. The data that fed the chart was sorted by the increasing percentage of students enrolled in FRL. All data comes directly from the Michigan Department of Education.

The black line is the computer generated trend line for the percentage not meeting standards, with the key point being it clearly correlates to percentage enrolled in FRL.

The correlation between lower proficiency and lower socioeconomic status raises many questions as our country (and state) increases the stakes for schools whose test scores are trending down while their FRL enrollment is increasing.

Contrarians are quick to accuse public school educators of using poverty as an excuse for low academic expectations, often followed by anecdotal evidence of districts or schools that defy this trend. There will always be exceptions – frankly in both directions. The broader point of the trend, however, is undeniable. This was the topic of my blog entry “Which came first? Bad schools or poverty.”

Does this mean we use poverty levels as an excuse for low performance or low expectations? Of course not. Does it mean we ought to be careful about designing accountability systems that place significant weight on standardized test results? I think so.

We have a variety of options to assess our efficacy as a public school district. I offered many in this blog entry in which I emphatically encourage our community to embrace the accountability dimension of the education reform movement, but do so in terms of our choosing.